GEBIEDONLINE: Community Tech in Practice

by Ruurd Priester, Design Researcher at Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL)

A Dutch online community platform in cooperative ownership

Gebiedonline is a Dutch online platform which connects people in local neighbourhoods, or those with shared interests. This article outlines how a platform like Gebiedonline supports residents to structurally contribute to the liveability of a neighbourhood. Below we describe the emergence and development of the platform, as well as the ownership and governance structures involved.

Gebiedonline was created by residents of IJburg, a district in Amsterdam. IJburg is a relatively new district consisting of a series of artificial islands on the east side of the city, initially constructed in 1999. Quite soon after the first neighbourhoods were completed in 2014, a network of active progressive residents emerged (‘IJburg Dreams, IJburg Does’). These residents were committed to the sustainable and social character of their neighbourhoods. Soon after this network was established, Michel Vogler, a resident of IJburg, took it upon himself to create a website — called halloIJburg.nl — through which residents could communicate and exchange information.

Using the resources afforded to him by his own IT company, Michel developed the platform in a continuous rapid-prototyping approach: seeing as Michel was a resident of IJburg, halloIJburg.nl was designed and built in a demand-driven manner from the very beginning. Active participation in his own community meant that decisions about the platform’s functionality were made via ongoing conversations with his neighbours and friends. The website was also run without strict roles or hierarchies: there was no central editorial staff — as long as a resident had a profile setup on halloIJburg.nl, they had full administrative access, and were able to add and change content. This is very much still the case today.

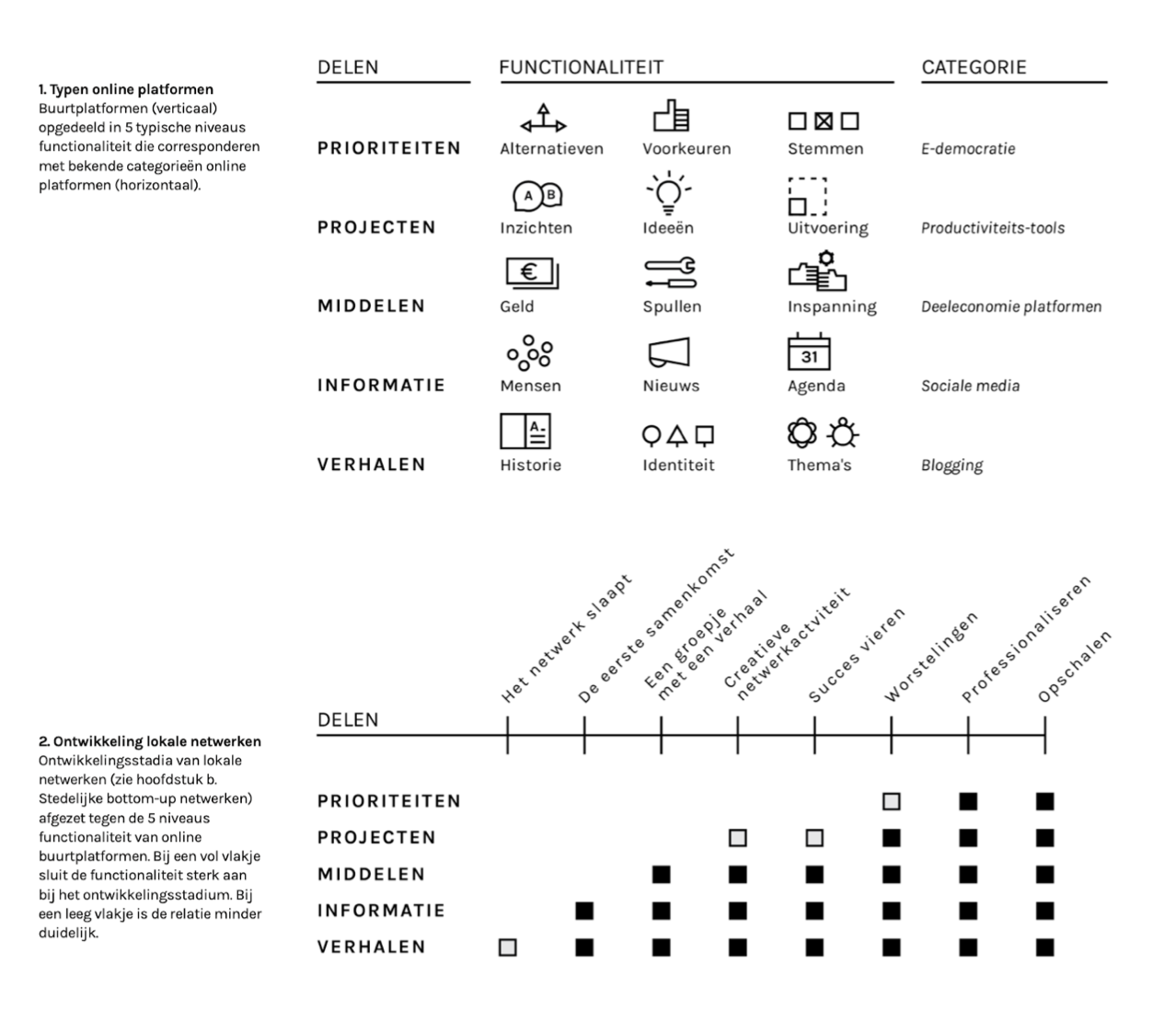

Over time, Michel developed a simple sharing model, layered like so:

Information sharing: news updates, contact details, and so on.

Resource sharing: money, possessions, and capacity

Project sharing: insights, ideas, and collaborating on execution

Decision sharing: voting on alternative systems for the neighbourhood, and shifting priorities

These layers closely resemble existing well-known platforms and tools: social media, resource sharing (such as Peerby, where you can rent other people’s possessions), productivity tools, and e-democracy tools. The emergence and crystallisation of these layers demonstrates just how valuable halloIJburg became for its community.

The first two layers (information and resources) presented themselves fairly quickly. The development of the next two sharing layers (project sharing and decision-making) took place in an exploratory and rather fragmented way via a series of projects involving those from the local government. These included initiatives such as managing the neighbourhood budget, and maintaining the right to challenge the publication of resident data.

During this stage of development, users of halloIJburg.nl increased into the thousands. This happened without direct marketing, and was mainly due to the popularity of a regular newsletter aimed at the community. Eventually, people from outside IJburg (and even in some cases outside of the Netherlands), began sending Michel requests to copy the platform for use in their communities.

This rise in interest and popularity spurred on the decision to formally establish the platform as a cooperative. In 2015, Michel and I began working together to make this a reality. With my experience in digital design and as an active social entrepreneur, and Michel’s existing knowledge of the platform itself, we were able to launch Gebiedonline. The platform was altered to be more generally applicable, and by 2016 we had five members from other local networks. Members pay an annual fee to use the platform, adapt it to their specific needs., and have a say in how it’s maintained.

Using our collective knowledge on cooperatives, we formed a board consisting of a treasurer, secretary, and chair. We also came up with a list of guiding principles to safeguard the underlying values and culture of the platform:

1. Common interest. The cooperative is an idealistic organisation. We are building something big together and that shared interest is always central.

2. Entrepreneurial. The cooperative is a business. By this we mean that all members are prepared to take risks. We are constructively critical and above all see opportunities.

3. Focus on making. We are a manufacturing club, not a talking shop. At least 80% of the energy we put into the cooperative returns to the Gebiedonline platform.

4. Embracing diversity. We cherish the differences between members. Members bring unique knowledge and opportunities. The sum total of people creates the cooperative.

5. Flexibility. We look for reusable patterns and for relevant differences between networks. We facilitate differences through modules, variables and style sheets.

6. Simplicity and elegance. The members know the pitfall of complexity. Thinking too much in terms of exceptions creates unnecessary complexity, resulting in delay.

7. Direct and open communication. We talk with each other, not about each other. If something doesn't go well for someone, or doesn't feel right, you can trust that you know about it.

Members play a significant role in how Gebiedonline is governed: there is a mechanism set up for them to freely make feature requests, and there is a regular meeting where complex considerations are discussed. This often concerns questions about whether functionality is in line with the principles of the platform, such as allowing advertisement, or ensuring that increased functionality does not decrease user experience. Members are also able to both add and access new features, without consensus. Finally, members do not have any form of transferable ownership in Gebiedonline — if they choose to revoke membership, they will not have any ‘shares’ to sell.

The chair’s role is simple: to ensure that decisions are made smoothly. This is done on the basis of consent: a proposed decision is always adopted, unless someone has a serious objection. Gebiedonline is now five years old. The cooperative and the online platform have developed organically, with no official marketing strategy, and no adjustments made to the management structure and governance model — and the members are very happy with it. There are now forty-four networks as members, spanning across cities and villages throughout the Netherlands, with approximately twenty-five thousand users with a profile and many more without.

There’s also been a rise in memberships which represent networks connected by shared interests. These include networks which focus specifically on ‘clean energy transition’ (for the whole of Amsterdam) or ‘a democratically governable energy market’ (for the whole of the Netherlands). It is extremely notable that even within a platform governed by a flat hierarchy, the design serves the needs of both a local community, and a community built around a common goal.

In 2017, as a research fellow, I conducted fairly extensive research into the use of online platforms in neighbourhoods in Amsterdam. At that time, I also organised talks between representatives of bottom-up networks and the municipality. It emerged that demand-driven development, local ownership and an integrated approach are crucial for success. In more detail, this research resulted in thirteen recommendations for (online platform supported) local cooperation:

Organise participation where it is primarily relevant for city dwellers: the block, the street, the square or the neighbourhood where people live and/or work.

Make sure that distant and/or incomprehensible choices or structures at high levels of scale do not frustrate participation at the small scale.

Interpret the stimulation of civic participation as the organisation of a participatory process in which the role and contribution of all those involved are clear.

Do not start ad-hoc projects, and clearly show how subprojects are connected and contribute to a vision, ambition and strategy.

Organise the cooperation as a short-cycle and learning process, through which people can achieve successes together, which radiate to everyone, so that trust is built.

Recognise the law of the 90-9-1 rule: on any given issue, roughly 1% of people take an active stance and 9% behave as followers and the remaining 90% behave as passive lurkers.

As far as possible, bring all those involved in the network to an equal and high level of information. Make the information easily accessible and usable.

Recognise that the usability of the online platforms is a vital success factor and that this requires a well thought-out co-creation process and professional design expertise.

Be aware of the historical perspective and seek connection with existing networks and initiatives, without taking ownership.

Increase the possible impact of the cooperation by steering towards the formation of interdisciplinary and multi-stakeholder teams.

Create room for collaborating networks/teams to come up with creative and fundamentally better solutions. Avoid cluttering up the solution spaces.

Search with the networks for the really urgent issues. Make sure that the ‘what is in it for them?’ is in the foreground and clear to all network partners.

Ensure strong, appealing and intensive communication of the story of 'the why' and provide regular updates from and for all stakeholders.

Cooperation between change agents in bottom-up networks and people from local governments is often difficult. The government works within the very structures that very likely pose a barrier to affecting any change. Many of the recommendations above concern the conditions under which the cooperation can work. In essence, many conditions are about building trust.

Officials often ask about the added value of online platforms for neighbourhoods and the networks that work hard for liveability. This is a strange question for the people in the networks, because the value seems obvious — self-organisation via online platforms is what characterises the 'modern world', afterall. Better neighbourhoods are created by knowing each other, exchanging information, and working together. An online platform makes this possible continuously and across the boundaries of organisations. The added value is also apparent in the four layers of sharing discussed above. The quality of life within a neighbourhood — now and for future generations — increases when engaged citizens and civil servants work together on the basis of trust.

If you want to learn more about Gebiedonline, the website contains further information about the functionality and the participating networks. With the help of Google Translate, this can be easily understood by non-Dutch speakers.

The study I refer to is Our online platforms. How online platforms threaten and can strengthen democracy. It is only available in Dutch.

Essays exploring how communities work with technology and innovation to shape better places.

Introduction: Creating Value that Sticks to Place

Realising the Power of Place-Based Community Innovation in the UK

How Can We Create Community Alternatives to Big Tech Infrastructures?

Participatory Community Technology

Interview with Wings, Ethical Delivery Coop

Gebiedonline: Community Tech in Practice

Interview with Community Care Connect, the Community-Powered Homecare Platform